Red-Light Realities: Trisha Mishra on Menstrual Dignity and Sex Workers’ Rights in India

Navigating the Margins: Social Work and Gender Justice in India

Social work in India often involves navigating deeply layered margins—spaces where official policy meets lived experience, and where caste, gender, class, and systemic power intersect in complex ways. One such space is the red-light area: not just a site of survival, but a parallel world where quiet networks of care, resistance, and resilience thrive.

As a gender researcher, I have spent significant time documenting the lives of transgender individuals and sex workers in India—communities whose stories speak of both profound pain and remarkable perseverance. These experiences reveal how gender inequality, poverty, and social stigma continue to shape the realities of those pushed to the peripheries.

I came in contact with Trisha Mishra, a dedicated development practitioner based in Shimla, through a common connection. Her grassroots work with marginalized communities—including women in red-light districts and rural villages—offered a compelling perspective on ethical social work. Her insights, grounded not in abstract theory but in the realities of the field, prompted deeper reflection on the meaning of solidarity, listening, and witnessing in spaces often excluded from mainstream social development discourse.

Meeting Trisha: A Turning Point in Gender Research in India

At a moment when my engagement with gender studies—particularly the study of abjected lives—was entering a deeper, more reflective phase, I found myself seeking new ways to understand the invisible architectures of power that shape Indian society. I was in the midst of interviewing transgender individuals, many of whom were navigating life through sex work, when a significant shift occurred in my research journey.

Unlike the individuals I had spoken with earlier—whose stories bore the weight of marginalization—Trisha Mishra brought a different lens. A development professional with years of on-ground experience, she offered a practitioner’s view that was at once pragmatic and deeply empathetic.

We connected through a mutual acquaintance and soon arranged to meet. That conversation left a lasting imprint on me. It wasn’t just another interview—it was an encounter that challenged my assumptions about what it means to “collect” narratives. Trisha’s grounded, respectful approach urged me to reconsider not only the methods I used in fieldwork but also the ethics of researching marginalized communities.

She reminded me that fieldwork is not solely about documenting pain. It’s also about recognizing everyday acts of care, dignity, and survival—qualities that often remain invisible in mainstream accounts of sex workers and transgender communities in India.

Trisha Mishra: A Quiet Force in Social Work and Community Transformation in India

Trisha Mishra is a deeply committed development professional in India, whose grassroots work reflects not just strategic acumen but a profound ethic of care. With over eight years of experience across the country’s social sector, she has engaged with some of the most vulnerable communities—including tribal groups, sex workers, adolescents, and women—through initiatives that blend compassion with actionable change.

Currently serving as Program Associate (District) with Spectra/HPSRLM in Himachal Pradesh, Trisha plays a key role in strengthening Model Cluster Level Federations under the State Rural Livelihood Mission. Her work here involves program oversight, strategic planning, and community mobilization—all anchored in participatory development practices.

Previously, Trisha held impactful roles at Jagori Grameen, Life Project 4 Youth (LP4Y), and Sari Bari Pvt. Ltd., where she helped conceptualize and lead Project Masik Mantra—a groundbreaking intervention on menstrual hygiene and dignity in red-light districts. This initiative earned national recognition for its innovative, community-driven approach to addressing menstrual inequity.

Her academic journey includes a Master’s in Social Work from IGNOU and ongoing postgraduate studies in Tribal Development Management at NIRDPR, Hyderabad, demonstrating her commitment to continuous learning.

What sets Trisha apart is not just the breadth of her experience, but the ethics and empathy that shape her practice. In a field often dominated by performance metrics and targets, her leadership style—quiet, rooted in relational care, and committed to transformative listening—serves as a rare and powerful model of community transformation in India. Her work reminds us that real social change grows not from visibility, but from trust, presence, and long-term solidarity.

A Conversation Beyond Metrics: Listening to Trisha Mishra

Our conversation with Trisha Mishra unfolded less like a formal interview and more like a shared reflection—full of chai, long pauses, and layered memories. She spoke not in jargon but in lived stories, shaped by nearly a decade of working with vulnerable communities across India. Her words revealed not just strategies or frameworks, but the quiet convictions and ethical choices that have shaped her journey.

What emerged was a deeply human account—marked by uncertainty, resilience, and transformation. It was clear that Trisha’s work in social development is not driven by deliverables alone, but by a deep commitment to relational care, gender justice, and listening as a form of solidarity.

What follows is an excerpt from our informal yet illuminating exchange. In these reflections, Trisha Mishra offers a grounded understanding of social work in India, the challenges of working in fragile ecosystems, and her pioneering advocacy for menstrual dignity in some of the country’s most marginalized spaces.

Entering the Margins: Trisha Mishra’s First Encounter with the Red-Light Area

What inspired you to begin working with communities involved in sex work?

During my Master’s in Social Work internship in Kolkata, I had to select three organizations for field placements. While studying Women and Child Development, I kept encountering deeply entrenched gender inequalities. One thing that struck me was how casually and cruelly the word “prostitute” is hurled at women in everyday speech across India. It’s used not just as a label—but as an insult.

That pattern raised an unsettling question for me: Why is this word such a universal slur? What histories and silences does it carry? I wanted to understand the lives behind that label. That urge—to move beyond stigma and hear their stories—led me to begin working with communities involved in sex work.

Building Trust Where It’s Broken: Initiating Dialogue with Communities

Was there a particular experience that deepened your commitment to this work?

Yes. I grew up between Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, where festivals like Navratri and Durga Puja were central to my life. These celebrations honor the divine feminine in all her power. But what truly struck me was something I learned during my fieldwork in Kolkata—that the idol of Maa Durga is traditionally crafted using soil collected from outside the homes of sex workers. This soil is considered sacred, as if it blesses the goddess herself.

Yet, the very women associated with this “sacred soil” are excluded from society—stigmatized, ignored, and dehumanized. That contradiction stayed with me. It forced me to confront the deep hypocrisy in how society reveres the feminine in myth but shuns her in real life. It made me want to understand their lived experiences, not as objects of pity or taboo, but as people whose stories deserved space, respect, and listening.

Field Immersion: Navigating Red-Light Areas Across India and Beyond

What locations and communities have you worked with during your fieldwork?

My fieldwork centered on some of the largest red-light areas in India, particularly in West Bengal. I worked closely with communities in Sonagachi, Bagbazar, Khidirpore, Asansol, Bishnupur, and Kalighat—locations that form part of Asia’s most extensive red-light network. Each place had its own rhythm, its own codes of survival, and a unique relationship between vulnerability and resilience.

Beyond Bengal, I also engaged with sex worker communities in other Indian states. Later, I visited red-light districts in Bangkok, which has a very different context shaped by global sex tourism. The contrast between local and international dynamics deepened my understanding of how gender, poverty, and stigma intersect across borders, though the core issues—marginalization, lack of rights, and dignity—remain painfully similar.

Building Trust in the Shadows: A Day in the Red-Light Districts

What does a typical day in the field look like, and how do you build trust in these communities?

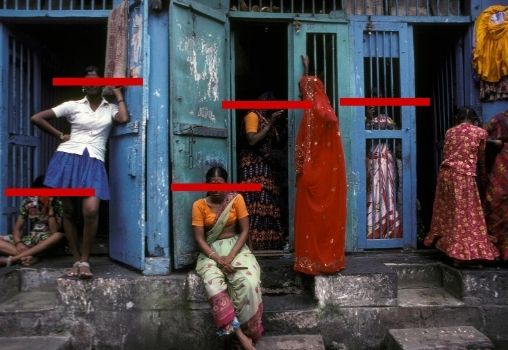

Working in red-light districts is emotionally intense and demands both resilience and sensitivity. A typical day began with navigating narrow alleys to reach brothels often marked by dim red or blue lights. These spaces are cramped—many rooms bearing signs of the previous night: used condoms, empty alcohol bottles, loud music lingering in the air.

Access wasn’t straightforward. Entry often depended on gaining the trust of brokers and “malkins” (brothel managers), who act as gatekeepers. Initially, I was met with skepticism, indifference, and sometimes outright hostility. Understandably so—many outsiders come and go, often with little accountability.

Building trust required consistent presence and relational patience. I returned day after day, sometimes just to sit silently nearby. Eventually, small gestures—sharing a cup of tea, listening without judgment, respecting their silences—helped bridge the gap. It wasn’t about grand interventions; it was about being genuinely present in a space marked by mistrust.

Emotional Toll and Ethical Tightropes in Fieldwork

What were some of the emotional and ethical challenges you faced?

Fieldwork in red-light areas took a deep emotional toll. Each day brought its own weight—children roaming unsupervised, women negotiating survival in dire conditions, and intoxicated men stumbling through alleyways. The harshness of these realities was difficult to process, especially when witnessed repeatedly.

I wasn’t spared the vulnerabilities either. On several occasions, drunk men harassed me, mistaking me for a sex worker. Even when they didn’t, the stares, the whispers, and the underlying assumptions were degrading. It reminded me that proximity to the marginalized often invites the same social stigma—a truth that many activists experience firsthand.

These moments forced me to confront not only ethical dilemmas about representation and intervention but also my own positionality. Despite arriving with the intent to help, I was never entirely separate from the social gaze that dehumanized the very people I worked with.

Allies on the Ground: Partnering with Organizations for Impact

Did you collaborate with any organizations during your work?

Yes, partnerships were essential. I collaborated with several organizations committed to both immediate support and long-term rehabilitation. These included Durbar, International Justice Mission, Justice Ventures International, Sari Bari Pvt. Ltd., Freeset Pvt. Ltd., and The Loyal Workshop.

Each organization played a different but critical role—rescue operations, aftercare, psychosocial support, and livelihood training that enabled women to transition into safer and more dignified professions. These alliances not only strengthened the scope of our work but also highlighted the importance of community-based, sustainable models in social work.

Breaking Stereotypes: Rehumanizing the Sex Worker Identity

What are some common misconceptions about people involved in sex work?

One of the most damaging misconceptions is that sex workers are inherently broken, helpless, or morally bankrupt. Such views strip away their individuality and dignity. The word “prostitute” is often used not just to label, but to shame—carrying centuries of moral judgment that reinforces exclusion.

In truth, many sex workers show immense resilience, adaptability, and care for their communities. However, society still resists seeing them as professionals entitled to rights, protection, and dignity. Even the shift in language—from “prostitute” to “sex worker”—remains controversial, though it’s a crucial step toward challenging stigma, ensuring social inclusion, and rehumanizing marginalized identities.

Layers of Inequality: Caste, Gender, and Class in the Sex Trade

How do caste, gender, and class influence entry into sex work?

Sex work in India is shaped by multiple axes of inequality—caste, gender, and class—which often determine who becomes most vulnerable to exploitation. Clients frequently inquire about a sex worker’s caste, revealing the deeply ingrained social hierarchies that persist even in illicit transactions. Upper-caste women are often fetishized or preferred, while Dalit and marginalized caste identities are stigmatized or made invisible.

Class and poverty play a significant role. Many women enter the trade due to economic desperation, limited education, or debt bondage. Gender inequality further restricts their choices—especially in communities where girls are seen as financial burdens. The demand for younger girls fuels child trafficking, often under the guise of job offers or early marriage.

In these conditions, women face reproductive health issues, emotional trauma, and a high risk of substance dependence, all while lacking access to basic healthcare or legal protection. Addressing these interlocking systems of oppression is essential to any meaningful intervention in the sex trade.

State of Neglect: Law, Institutions, and the Broken Promise of Support

How do law enforcement and public institutions affect the lives of sex workers?

Despite official claims of support, sex workers continue to suffer from institutional neglect. Basic necessities—like sanitation, clean drinking water, and accessible healthcare—are often absent in red-light districts. Legal protection is either unavailable or inaccessible, leaving women vulnerable to abuse, eviction, and police harassment.

Law enforcement often acts as an instrument of intimidation rather than support. Raids can be violent, and corrupt officers sometimes exploit the very women they’re supposed to protect. Public institutions fail to deliver consistent aid, and their presence is usually symbolic or limited to token outreach.

NGOs working in these areas face intense resistance from local power structures—be it criminal networks, political actors, or brothel owners—making sustained impact difficult. This failure of the state to protect its most vulnerable citizens reinforces cycles of poverty, exploitation, and invisibility.

Marked Lives: Stigma, Criminalization, and the Daily Struggle for Dignity

Do stigma and criminalization affect daily life for sex workers?

Absolutely. Stigma against sex workers is pervasive, shaping how they are treated not just in brothels, but in hospitals, police stations, and even schools. Society often assumes they are immoral or deserving of their suffering, which strips them of basic dignity.

Even when a woman tries to exit sex work, criminalization and lack of documentation—like ID cards or address proof—block her path. Without access to education or stable employment, reintegration becomes nearly impossible. Surveillance and suspicion follow them into new neighborhoods, re-inscribing their identity as outsiders.

The criminalization of marginalized communities doesn’t just enforce legal consequences—it deepens social alienation. Dignity becomes a daily struggle, not just a long-term dream.

Owning the Narrative: Voices from Within

How do the people you work with view their own narratives and lives? What did they want the outside world to understand?

Sex worker identity is complex and deeply personal. Age, experience, and circumstance all influence how women in the trade view themselves. Many older women speak of coercion, abandonment, or extreme poverty as the starting point. In contrast, some younger women say they have chosen this path—seeking financial independence, personal autonomy, or the freedom it offers outside traditional jobs.

Yet across generations, there’s a shared rejection of the term “prostitute,” which is seen as degrading and reductive. They prefer to be called sex workers, a term that affirms their agency and labor. This shift in self-perception among marginalized communities is not just linguistic—it’s political.

In Bengal, there are ongoing efforts to secure legal rights of sex workers, including formal licensing, access to identity documents, and inclusion in welfare schemes. These steps are crucial not only for protection, but for restoring dignity and recognition to lives that have long been sidelined.

Responsible Representation: Depicting Sex Work Beyond Stereotypes

How should sex workers be represented in media, literature, or academic work?

The representation of sex workers in media and literature has historically been distorted by moral judgment, voyeurism, or pity. In Bengali literature, there were attempts to explore the emotional lives of sex workers, but colonial influences and postcolonial nationalism further demonized or victimized their image. These narratives shaped public perception, often portraying sex workers as either tragic figures or corrupting forces.

Today, some films and documentaries are shifting the lens—highlighting agency, humanity, and the socio-political complexities surrounding sex work. However, many portrayals remain sensationalized, reducing their stories to trauma or erotic spectacle.

Ethical storytelling is essential. Writers, journalists, and researchers must engage with care, context, and consent. Representing sex work in literature or academic discourse means moving beyond binaries of exploitation and empowerment to reflect the full spectrum of lived realities.

Urgent Reforms: Legal and Social Change for a Dignified Future

What social or legal changes are most urgently needed?

Sex workers deserve more than survival—they deserve dignity, opportunity, and respect. Access to education, healthcare, legal rights, and sustainable employment is essential. The social inclusion of marginalized women must become a national priority. They should not be hidden or judged but welcomed into cultural, civic, and public life with equal rights.

Legal reforms for sex workers must go beyond tokenistic gestures. Policies should offer real exit pathways for those who wish to leave the trade and legal protection for those who choose to stay. Whether it’s access to housing, ID cards, or justice, every woman deserves the freedom to choose her future without fear, stigma, or coercion.

Seeds of Change: Stories of Transformation and Hope

Have you witnessed or contributed to any transformative changes during your work?

Absolutely. I had the opportunity to be part of several grassroots initiatives that sparked community transformation in red-light areas. Projects such as night schools for children, mobile health camps, and skill-building workshops empowered both women and youth. Perhaps most significantly, mental health support for sex workers through dedicated counseling centers offered safe spaces for healing, reflection, and resilience.

HIV support centers also played a crucial role, offering nutritional aid and emotional care. These collective efforts built a strong foundation of trust and visibly enhanced the emotional and psychological well-being of the community. Change came slowly, but steadily—with every conversation, classroom, and counseling session sowing the seeds of dignity, self-worth, and hope.

Trisha Mishra’s work shines a light on the unseen, unheard, and often forgotten lives within India’s red-light districts. Her journey, though fraught with emotional and ethical challenges, is a powerful testament to what committed social work can achieve. In listening deeply, engaging responsibly, and advocating fiercely, she becomes not just a witness but a participant in the struggle for dignity, rights, and justice.

The change we seek begins with recognition—of sex workers as individuals with agency, histories, and dreams. It grows through partnerships that center care, and it matures through policies that replace criminalization with compassion. While the path is long and layered, stories like Trisha’s remind us that transformation is not only possible—it is already underway. Each effort, no matter how small, becomes a step toward a more humane and equitable world.

Also Read

Why Periods Are A Bigger Challenge For Sonagachi’s Sex Workers

When Fiction Became Fire: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Truth That Changed America

Enid Blyton Birth Anniversary and Her Timeless Legacy in Children’s Fiction - BlogOpine

3 months ago[…] Red-Light Realities: Trisha Mishra on Menstrual Dignity and Sex Workers’ Rights in India […]